I recently had the pleasure of sitting down with Amanda Williams, Director of the MacArthur Memorial in Norfolk, VA. Amanda graduated from Randolph-Macon Woman’s College with a B.A. in History & Art History and later earned her M.A. in History from Old Dominion University. She began her career as an Archaeologist at Historic Jamestowne before serving as Education Manager for the MacArthur Memorial. She specializes in military history and women’s history and is also the host of the MacArthur Memorial Podcast and the World War I Podcast.

In our time together, we covered a wide range of topics – from culture wars and AI to the man himself, General Douglas MacArthur, and the responsibility of stewarding a site that strives to deliver a well-rounded interpretation of his complex legacy. I was inspired by Amanda’s reflections on her role as the Memorial’s director, military history’s role in the museum field, and the role of museums in our shared global future. Here are some highlights from our conversation.

Carrie: I have to start here because I’m so curious – why is the MacArthur Memorial, a site about the life of an Army general, in Norfolk, VA, which is a Navy town?

Amanda: MacArthur’s mother was from Norfolk, and they were very close. He was born in Little Rock but, as the son of a career army officer, spent his young life and 60+ year military career traveling from post to post.

C: Well, that explains what brought the Memorial to Norfolk, but what brought you here and to museums in general?

A: I’ve always been fascinated with history, and I have a lot of veterans in my family – among them, some who made the ultimate sacrifice, so military history isn’t an abstract thing to me. It has a personal connection. Beyond that, there’s something special about holding a piece of history in your hands or standing on the spot where something amazing or tragic in history happened. How can you not want to share an experience like that? Obviously, in museums, we can’t let people hold everything in the collection, but we can try to bridge that gap.

C: As a fellow history nerd, I can definitely relate. Something I have significantly less experience with is running a museum, though. What’s that like?

A: Directing really comes down to three main tasks – managing resources, cultivating partnerships, and formulating the strategic vision for the museum. When I started my career, I think I looked at the directors of the organizations I was with and wondered, what do they do? When you’re out in the field, you think, look at us archaeologists in the field finding stuff, or look at us in education providing these outreach programs. We’re doing a lot. What do they do? Now, I appreciate what all those men and women I worked for were doing because it’s a full day, a full night, and full weekends. I don’t get to work as directly with the public or with the historic objects anymore, but it’s very fulfilling work.

C: Well, managing a site like the MacArthur Memorial must keep you on your toes. What are some of the things that make it unique?

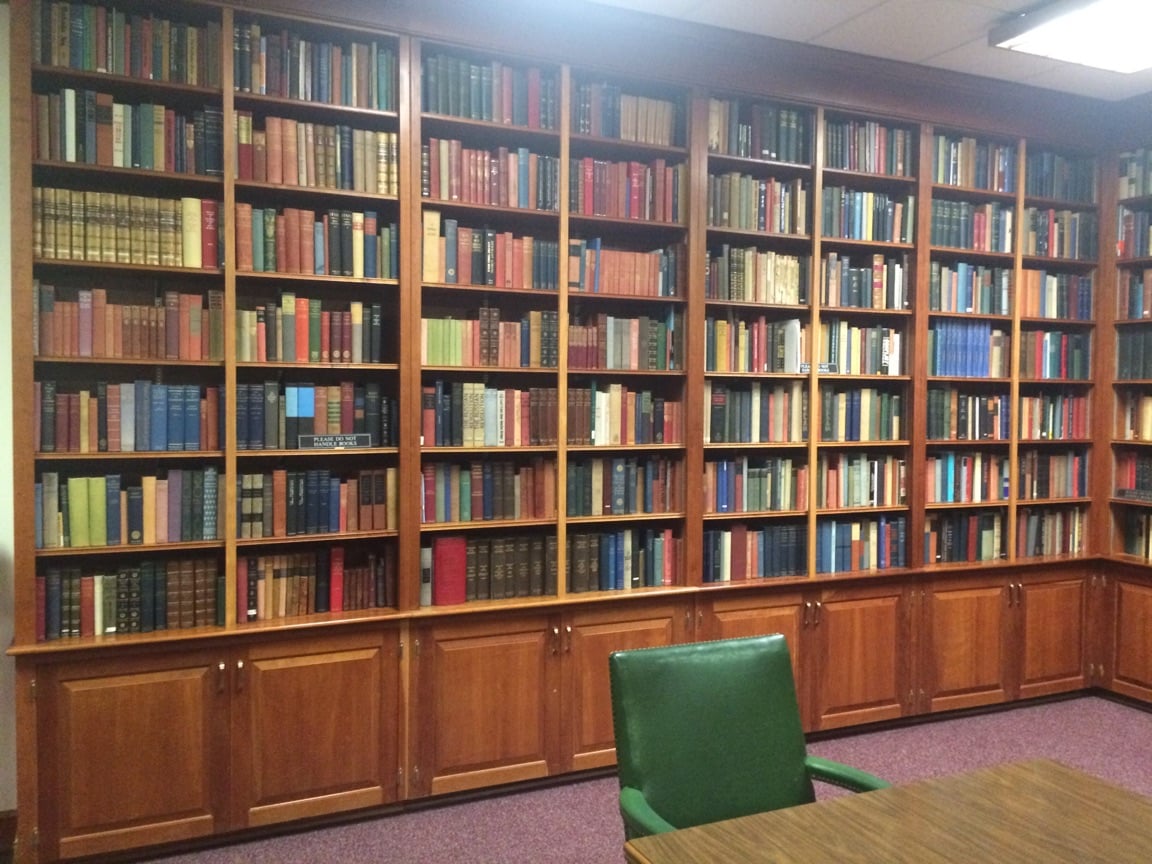

A: The MacArthur Memorial is often compared to a presidential library in terms of its function. Obviously, it’s not, although I think General MacArthur would have really enjoyed that comparison. We are a three-building complex that takes up an entire city block with the museum, visitor center, and research library. We have over 2 million documents, 100,000 photos, and 40,000 books – anything from the 16th century to the end of the Korean War. MacArthur is a very polarizing figure. If you don’t like him, we don’t mind. We just want you to dislike him for historically accurate reasons and vice versa. The Memorial is not a shrine. We are the site of his tomb, and that is a special place here, but we are also a dynamic research and education center, which helps make us a trusted source.

Image courtesy of The MacArthur Memorial

Image courtesy of The MacArthur Memorial

C: Military history certainly has no shortage of polarizing figures. What role do you think military history plays in understanding the present and thinking about the future?

A: I hate to be gloomy, but there will always be conflict. I don’t believe history repeats itself because that ignores human agency, but what does appear constant is human nature, so I think we can safely assume there will always be conflict. And if there is conflict in the future, then we need to understand it. Military history gives us that intellectual framework to be able to understand those connections and to be able to explore the cause-and-effect relationships surrounding war.

C: Like any discipline within the larger history field, military history has its fair share of complex and challenging topics. How does the Memorial approach interpreting things that require more sensitivity or care?

A: Obviously, MacArthur can be a polarizing figure, and years ago, I was advised to avoid or downplay parts of his story. Our team decided not to follow this advice, and instead, we do our best to share the difficult parts and the triumphs in his story. One example is our new special exhibit, “The Price of Unpreparedness.” It tells the story of the 90,000 Americans and Filipinos who were left behind in the Philippines in 1942 after MacArthur was ordered to Australia. This was not a high point in his career, and no one in the US has ever tackled this disaster in such depth before. The reason we were able to tell it is that, even though a lot of those POWs that survived were not necessarily MacArthur fans, they respected the Memorial and they knew that if they gave us their artifacts and personal papers, we would take care of them and we would tell their story whether it was a high mark of his career or not.

C: Taking a step back to look at the museum field as a whole, what are some of the challenges or opportunities that you see ahead?

A: AI is one of the things I think about the most and am always trying to explore. I see incredible potential there for museums but also major issues in terms of history and museums, the visitor experience, and even things like staffing. Another thing facing us is the incredible responsibility of public trust. The American Alliance of Museums regularly conducts surveys that show that people consider museums to be the most trusted source of public information. It’s very tempting sometimes to get involved in public debates and culture wars, but we have to be above the fray. That doesn’t mean you don’t link the past to current events or invite audiences to look at what you have and try to understand their world through that lens, but in an increasingly divided world, we still have to be for everyone. It’s a very difficult line to walk, but we cannot lose that public trust. The community needs us more than ever.

C: That’s so true, and what a responsibility and an honor it is to be a steward of that trust. We’re out of time, but any closing thoughts you’d like to share?

A: I think all I have left to say is that MacArthur merits a second look. If you think he was a coward, if you think he was incompetent, he merits a second look. If you glorify him, I would encourage a critical examination. Overall, though faults and triumphs all weighed together, I think that MacArthur was a net positive for the world. I know the “great man” theory of history is very much out of fashion, maybe forever, but I do think sometimes it can be an interesting lens through which to understand our past and even our present, and General MacArthur is an interesting person to explore that through.